Let's Teach Young People Hope—Not Doom

Education expert Bruno Manno argues that when educators present social and ecological problems as intractable, this can foster hopelessness in students. This school year, he urges, we should teach students that problems can be solved, not merely bemoaned.

“Don’t teach your kids to fear the world,” writes Arthur C. Brooks, public intellectual and happiness researcher at Harvard. “Teaching them that the world is a dangerous place is bad for their health, happiness, and success.” This is a great message for K-12 school educators to remember as they head back to school this year. There is no doubt teachers face a heavy task. They are not only delivering content or raising test scores. They are shaping the hearts and minds of a generation grappling with what can feel like relentless gloom.

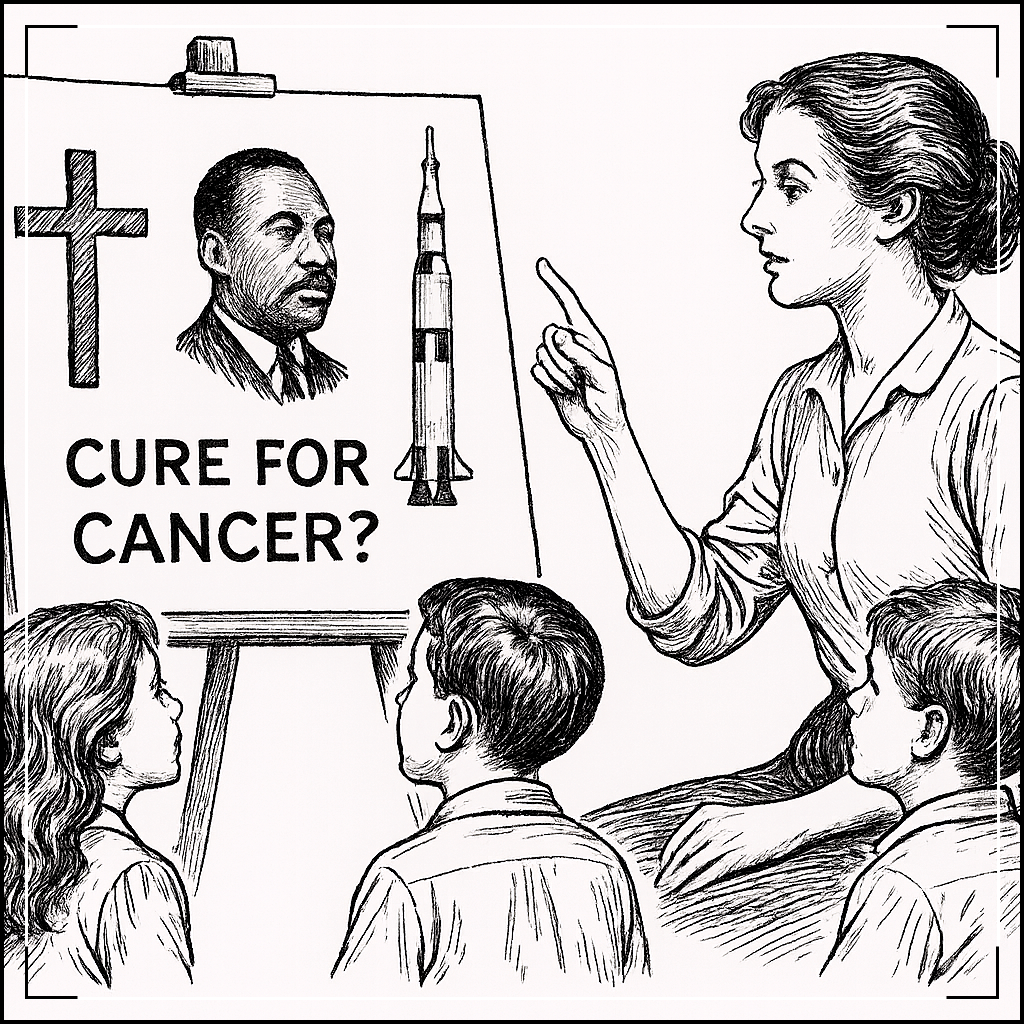

Turn on the news—or browse the average social studies curriculum—and it is hard to escape the drumbeat of crisis. Climate catastrophe, democratic collapse, political assassinations, economic inequality, racial injustice, mass shootings, mental health epidemics, and disruption from artificial intelligence. The list is long and, for many young people, it is overwhelming. Educators rightly want students to be aware of the world’s problems. But in the process, they may unintentionally teach gloom and despair.

Today, it is not enough for educators to sound the alarm. Rather, the job of teachers and professors is to equip young people with the mindset and motivation to face an uncertain world with agency, purpose, and—above all—hope. Here are five ways to do this during this new school year.

The first step is to recognize that hope is more than an attitude, but a practice that can be learned.

The late psychologist and Gallup senior scientist Shane Lopez, in his 2013 book Making Hope Happen, defines hope not as wishful thinking or blind optimism but, rather, as a virtue that involves a strategy that can be learned and lived. He shows that hope consists of three elements: goals, or knowing what one wants to achieve; pathways, or identifying realistic routes to those goals; and agency, or believing one can make progress, even when obstacles appear.

These three pillars—goal setting, problem solving, and personal belief—offer a powerful antidote to the cultural script of powerlessness. Lopez’s research shows that high-hope students get better grades, experience less anxiety, and are more likely to graduate and thrive. “Hopeful students,” he writes, “see the future as something they can shape.”

Contrast that with what too many students absorb from well-meaning but doomsaying educators: the idea that the systems are rigged, the planet is doomed, and any personal ambition is either naive or complicit. The result is not engagement but paralysis. If children go to school to prepare for life, they must believe that life is worth preparing for.

Second, hope matters now more than ever.

Lopez’s insights are even more urgent in today’s context. In a rapidly changing world—where political polarization and technological disruption shape the headlines—young people need more than determination. They need a vision of the future in which they can believe. Neuroscience research suggests that hope is associated with activation in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, a region linked to cognitive flexibility, problem-solving, and goal-directed behavior. In short, hopeful students do not just feel better. They think better.

Moreover, hope has ripple effects beyond academics. It is linked to better health outcomes, stronger relationships, and more resilience in the face of adversity. A hopeful student is more likely to plan, delay gratification, and avoid self-destructive behavior. This hopeful student is also more likely to help others, creating a virtuous cycle of prosocial engagement. In this sense, cultivating hope is not just a psychological intervention but a civic responsibility.

Third, move from despair to agency.

None of this means we should sugarcoat reality or ignore injustice. However, there is a difference between teaching about challenges and teaching that challenges are insurmountable.

The difference lies in framing. Do we present students with problems as crushing burdens or as solvable puzzles? Do we teach them about climate change only as a catastrophe or also as an opportunity to work on carbon capture, clean energy, or resilient agriculture? Do we focus only on systemic inequities or also introduce them to reasons for gratitude and shine the spotlight on people and movements that have made a lasting change for the better?

Educators who frame problems through the lens of hopeful engagement—“Here’s how we got here, and let’s figure out how you might help fix it”—are not denying reality. They are offering students the dignity of being taken seriously as civic agents and future contributors.

Fourth, hope strengthens individual agency and purpose.

It is essential to recognize that hope is not equally distributed. Students growing up in poverty, in under-resourced schools, or in communities affected by violence and instability often experience what sociologists call "learned helplessness"—a belief that no matter what they do, their outcomes will not change. This mindset can be devastating, leading to disengagement, chronic absenteeism, and a host of long-term consequences.

Schools cannot control everything outside of their walls. Still, they can be places where young people encounter possibility—where they see models of success, receive consistent encouragement, and engage in experiences that build confidence and skills. For low-income students in particular, hope is a lifeline.

This means rethinking not only what we teach but how we teach it. Project-based learning, mentorship programs, community service, and internships are all ways to strengthen a student’s sense of agency and purpose. So is ensuring that every student has at least one adult in school who believes in them. The research that Shane Lopez discusses is clear. Hope grows and flourishes in relationships.

And finally, hope helps students develop a vocational identity.

One of the most effective ways to cultivate hope in young people is to help them develop a vocational identity. What kind of person do I want to be? What kinds of work are worth doing? What roles might I play in the world? These are deeply human questions, and research shows that they are also essential for psychological well-being and academic motivation.

When students can picture themselves in the future—when they can name a job, a path, or even just a kind of life they are working toward—they are more likely to persist in school, resist risky behavior, and invest in their communities. This is not just a career readiness issue. It is a mental health one.

Unfortunately, many schools do little to nurture this. Too often, vocational exploration is outsourced to a one-week unit in tenth grade or a scattershot career day. But forming a vocational identity is a developmental process. It requires consistent exposure to adult work, meaningful projects, mentorship, and opportunities to connect academic learning with real-world relevance.

This is where Lopez’s three-part hope strategy offers a practical blueprint. Help students set specific career and life goals, even if those goals change over time. Explore multiple pathways to those goals, including college, career and technical education, apprenticeships, and military service. Build a belief in their ability to succeed by highlighting stories of those who have overcome adversity.

The question is not whether we should prepare students for a complex world. Of course, we should. The question is whether we do so in a way that inspires paralysis or possibility. Every student deserves to be surrounded by adults who believe in their agency and who model hope as a virtue and strategy worth pursuing.

As we begin another school year, educators, parents, and other K-12 stakeholders should adopt hope as a top priority for learning. This does not mean ignoring urgent academic needs; reading, math, and attendance still matter. But it means placing those needs within a broader frame: Are we helping young people build a future they want to learn for?

Too many well-meaning adults confuse rigor with pessimism. But pessimism and cynicism are not signs of maturity. As Lopez writes: “Hopeful people are not naive. They are problem solvers. They believe that the future can be better, and they work to make it so.”

As the school year begins, here is a challenge for every educator: In addition to your subject matter goals, set a “hope goal” for your students. Ask yourself: What am I doing to help my students envision a meaningful future? What tools am I giving them to navigate setbacks? What models of contribution am I offering?

The new school year presents a fresh opportunity. Let us teach kids how the world works—but also how they can work in it. Let us teach them to see problems—but also to see possibilities. Let us teach them what’s broken—but also what is worth building.

Let us teach them how to plan, how to persist, and how to dream. And let us remember hope, like learning, is contagious.

Bruno V. Manno is a senior advisor at the Progressive Policy Institute, where he leads the What Works Lab. He previously served as a United States Assistant Secretary of Education for Policy.